HISTORY OF THE PERSIAN CARPET

At the beginning

Cultural Background:

The history of Persian carpet weaving stretches back thousands of years and is inseparable from Iran’s cultural identity, forming the foundation of persian rug history. One of the strongest reflections of this identity is found in the Shahnameh, the Book of Kings, which honors a civilization nearly 7,000 years old, positioned at the crossroads of Anatolia, the Caucasus, Transoxiana, and China. Despite invasions and cultural shifts, Persian values, arts, and craftsmanship endured, shaping iranian carpet history.

Origins of Carpet Weaving:

While Ferdosi’s Shahnameh suggests carpet-making began in prehistoric Persia, there is no surviving technical documentation from early dynasties, including the Safavids (16th century). Because of the absence of early physical examples, researchers rely on archaeology, historic texts, and miniature paintings to understand Persia’s earliest carpets and ancient persian rugs.

Discovery:

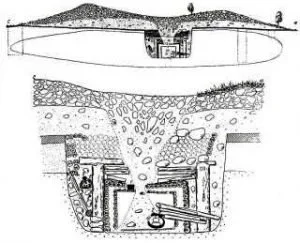

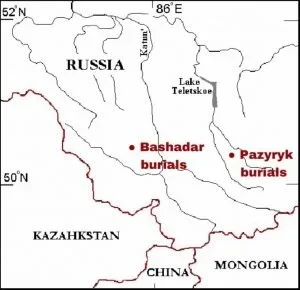

In 1949, archaeologists uncovered a remarkably preserved pile carpet inside a burial mound (“kurgan”) in the Pazyryk Valley of Siberia. The unique construction, wooden chambers, stacked logs, bark, branches, and seasonal freezing protected textiles for over two thousand years.

The Pazyryk carpet

Dimensions and Dating:

Size: 183 × 200 cm

Carbon date: 260–250 BC

Density: 360,000 knots/m²

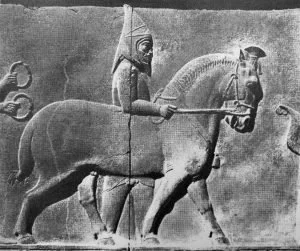

Design Influence:

The carpet includes motifs similar to Assyrian palace floors and Achaemenid sculptures, leading early scholars to believe it was woven in Persia. Later dye analysis revealed the use of Indian lac rather than Mediterranean kermes, shifting the theory toward a Central Asian origin, though Persian artistic influence remains evident within persian carpet history.

Bashadar Fragment:

In 1954, another fragment with 490,000 knots/m², tied using the Persian knot, was found 800 km west of Pazyryk. Carbon dating showed it predates the Pazyryk carpet by 130–170 years, offering rare insight into early weaving.

Supporting Evidence:

Tools associated with carpet-making, knives, beaters, weaving implements, have been found in Bronze Age burial mounds in northeastern Iran, confirming that weaving traditions existed in early Persia despite the absence of surviving carpets.

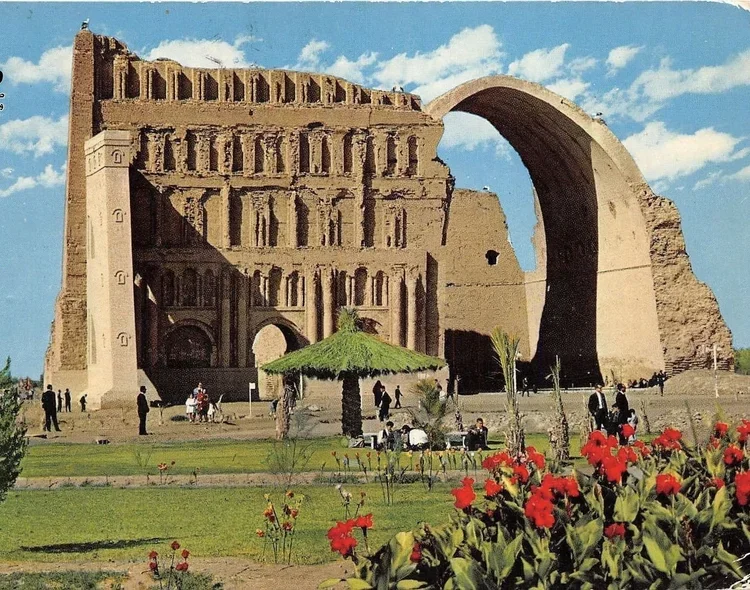

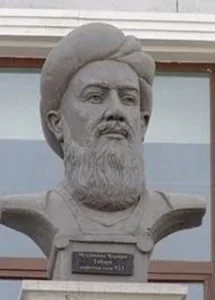

Historical Account:

Abu Jafar Tabari, writing during the Abbasid period, described a monumental carpet in the royal palace of Ctesiphon called the Khosrow Spring or Baharestan. Woven under Khosrow I, this carpet was one of four pieces symbolizing the seasons.

The Khosrow Spring carpet theory

Description:

Length: 140 meters

Width: 27 meters

Materials: Gold, silver, silk, gemstones

Theme: A lush spring landscape represented through woven imagery

Uncertainty:

While Tabari’s writings are respected, there is no surviving physical evidence, nor any primary sources confirming how the carpet was constructed. Some theories propose:

A jewelled kilim

A pile carpet with gems sewn onto a silk ground (similar to Polonaise techniques)

Legend holds that the carpet was cut into pieces and seized during the Arab conquest of Ctesiphon in 637.

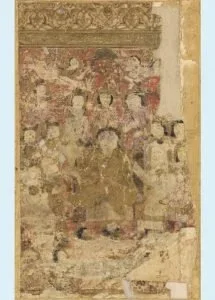

Ilkhanate & Timurid Influence:

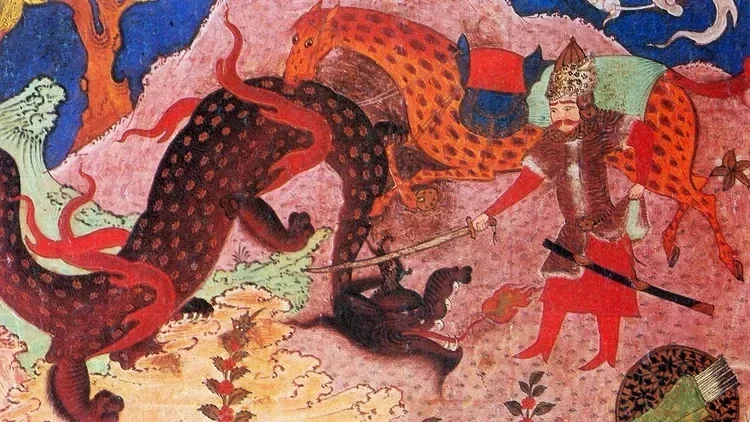

Persian miniature painting flourished by integrating Chinese, Hellenistic, and Byzantine aesthetics. These artworks are essential evidence for carpets that no longer survive and for persian rug patterns history.

Early 15th Century:

Depictions show:

Octagons

Diamonds

Similar to Anatolian Turkish carpets of the period.

Late 15th Century:

Designs evolved toward:

Curved vines

Medallions

Fluid symmetrical arrangements

These miniatures provide critical documentation of Persian carpet patterns during periods where few physical examples remain.

Carpets in Miniature Paintings

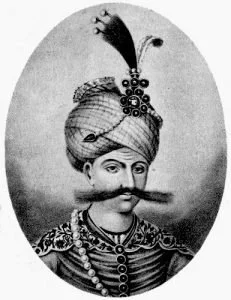

State-funded workshop number 1

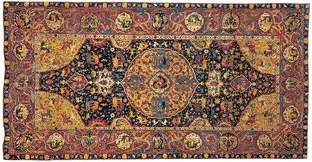

The Hunting Pattern Carpet

Significance:

The Hunting Carpet is the oldest Persian carpet with a woven date.

Discovery:

Founded in 1870 in the Quirinale Palace, Rome. It survives in fragments later restored using tapestry techniques

Dating Debate:

Two possible readings:

929 AH (1522–1523)

949 AH (1542–1543)

Stylistically, both dates align with early Safavid production.

Construction:

Wool pile

Silk warps

Cotton wefts

Likely woven in Tabriz

This carpet represents high court craftsmanship and early Safavid workshop organization in persian carpet history.

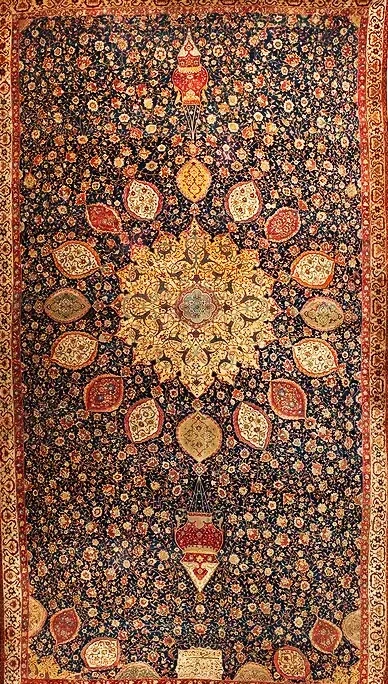

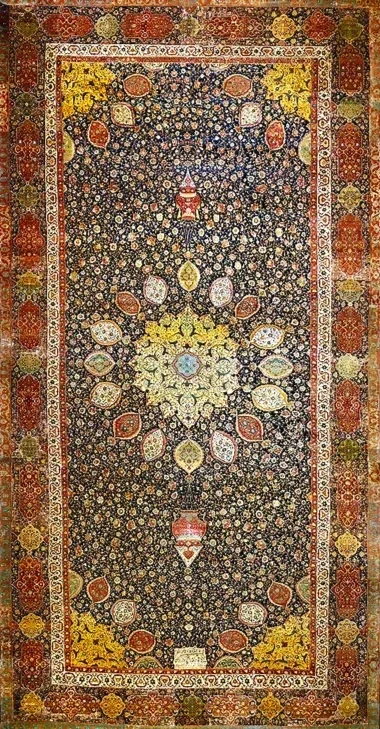

Overview:

One of the most iconic masterpieces in carpet history, woven by Maksud Kashani in 1539/40 (946 AH).

The Pair:

Two carpets were discovered in the shrine of Sheikh Safi al-Din in Ardebil. Today:

One is in the Victoria and Albert Museum

The other is in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Size:

Approximately 60 square meters, making it one of the largest and finest carpets of its era.

Attribution Debate:

While often linked to Tabriz, some argue for Kashan origins based on workshop characteristics.

The Ardebil Carpet

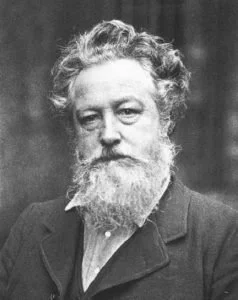

Journey:

Purchased by Ziegler & Co.

Promoted heavily by art dealer Edward Stebbing

Acquired through public fundraising led by William Morris

The Ardebil carpets remain among the most celebrated Safavid works globally.

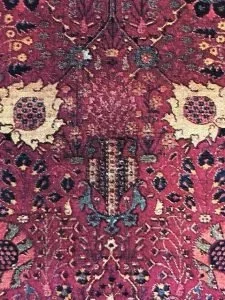

Origin:

Woven in Iran during the first half of the 16th century (Safavid dynasty).

Design:

Two large lobed black medallions

Four oval pendants radiating diagonally

Quarter and half medallions at edges

Deep red field depicting trees, plants, wildlife

Influences from early Safavid manuscript arts

Technical Detail:

Knot density: 720,000 knots/m²

Despite lacking inscriptions, the Chelsea Carpet exemplifies the refinement and artistic sophistication of early Safavid weaving.

The Chelsea Carpet

Use:

Displayed at the coronation of King Edward VII in 1902.

Origin:

Believed to be woven in Tabriz.

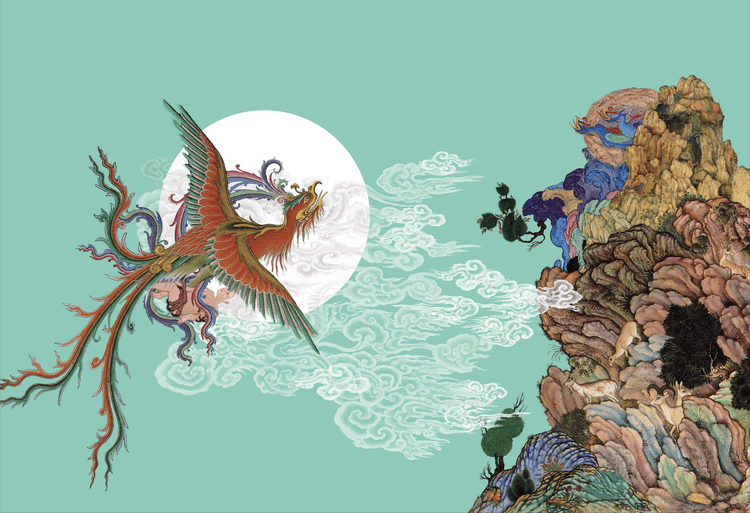

Design Motifs:

Blue cartouches symbolizing flowing water

Cypress trees and garden layouts

Dragons, phoenixes, and qilin (Chinese-inspired themes)

Size:

23 × 12 feet.

The British Coronation Carpet

Ownership History:

Owned by billionaire Marsden Perry

Later purchased by Jean Paul Getty

Donated in 1949 to the Los Angeles County Museum of Science, History and Art

This carpet is a rare example of cross-cultural symbolism blended within Persian design.

State-Funded Workshop No. 2

The Danish Coronation Carpet

Origin:

Woven in Isfahan in the 17th century.

Purpose and History:

This carpet served in the coronation ceremonies of Danish monarchs and is now preserved at Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen.

Size:

12 feet 2 inches × 17 feet 1 inch.

Design:

A royal-scale piece reflecting Safavid workshop standards, featuring refined floral, architectural, and symbolic motifs characteristic of Isfahan carpets of the era.

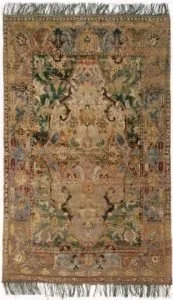

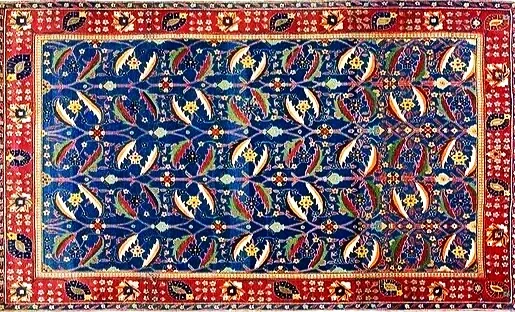

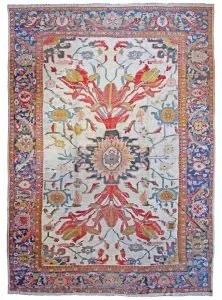

The Vase Carpet

Overview:

The Vase carpet group represents one of the most important series of Safavid designs, identifiable by vases, palmettes, rosettes, and an oblique lattice arrangement.

Surviving Examples:

Approximately 50 pieces and fragments exist today.

Structural Feature:

A defining characteristic of all Vase carpets is the triple-weft structure, two thin wefts paired with one thick thread.

Attribution:

Scholars debate between Kerman and Joshagan as the weaving centers.

Notable Provenance:

One of the most recognized Vase carpets entered the Victoria and Albert Museum through designer William Morris, who previously owned the piece.

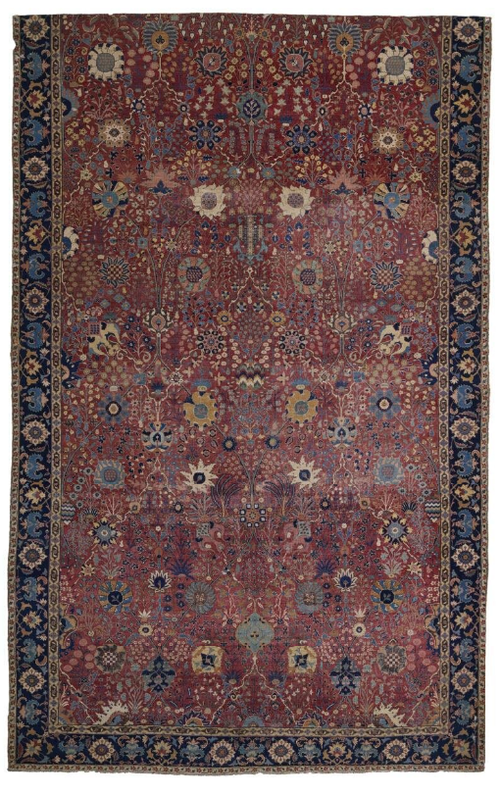

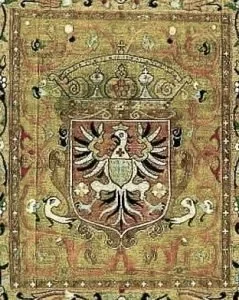

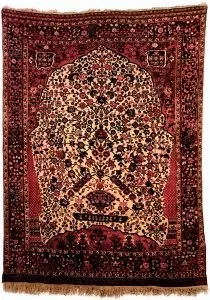

The Polonaise Carpets

Description:

Polonaise carpets are richly decorative Persian weavings made with silk pile combined with gold and silver threads.

Origin:

Woven in royal workshops near the courts of Isfahan or Kashan during the Safavid era.

Historical Misattribution:

Their name arose from a misunderstanding:

Many carpets bear Polish coats of arms.

When exhibited at the Poland Pavilion at the Vienna Expo, they were assumed to be Polish works.

Later documentation revealed they were commissioned from Persia by King Sigismund III of Poland around 1601–02 as part of a royal dowry.

Surviving Pieces:

Around 230 Polonaise carpets are known to exist today.

Origin and Early History:

The carpet’s early life is unclear, but by 1621 it was stored in the Ottoman Imperial Palace in Istanbul.

Capture and Ownership:

Seized as war booty after the Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Khotin.

Taken by Prince-General Sanguszko of Poland and kept within the family for generations.

Exhibitions and Scholarship:

First publicly shown in 1904 in St. Petersburg.

Displayed prominently at the 1931 International Exhibition of Persian Art in London.

Studied extensively by Arthur Upham Pope, who also exhibited it for 23 years.

Later History:

Displayed during the Shah of Iran’s visit to the Asia Institute in New York in 1949.

Pope identified a matching design in a war vest of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, confirming a shared Persian source.

Sent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1954, where it remained until 1995 before being sold.

The Sanguszko Carpet

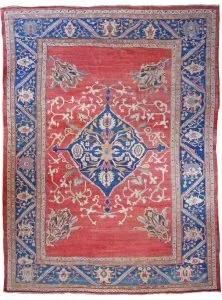

16th Century Medallion Tabriz Carpet

Auction Record:

Sold at Christie’s London in 1999 for $2.4 million.

Attribution:

Believed to have originated from Tabriz during the 16th century.

Size:

6.60 m × 3.58 m.

Provenance:

Originally owned by Baron Nathaniel Rothschild of the UK and later passed to Baron Albert Salomon Anselm von Rothschild of Austria.

The carpet was reportedly stolen during World War II and later purchased by Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani.

It is now housed in the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

Kirman Vase Carpets

Christie’s Sale (2010)

A Kirman vase-pattern carpet from the mid-17th century sold for €7.2 million at Christie’s London.

Sotheby’s Sale (2013)

The most expensive Persian carpet ever sold:

$33.7 million

Believed to originate from Kerman, mid-17th century.

Known as the William A. Clark Carpet, named after its American owner, Senator William A. Clark.

Features distinctive sickle-shaped leaves.

Measures 2.67 m × 1.96 m.

This sale set a global auction record for any carpet.

The Fall of the Safavid Dynasty and the Decline of the Carpet Industry

After the death of Abbas I, the Safavid Empire entered decline.

Key Events:

1722: Afghan forces led by Mir Mahmoud captured Isfahan, devastating the capital.

Royal carpet workshops, dependent on state patronage, collapsed.

Rug weaving survived mainly in rural and nomadic communities.

Afshar Influence:

After Mir Mahmoud's assassination, Nadir Quli Beg (later Nadir Shah) rose to power.

His military campaigns in Afghanistan and India brought Persian carpets back to Iran as war spoils, influencing village weaving traditions across the country.

Design Exchange Evidence:

Herati patterns appearing outside Khorassan.

Mihrab motifs in Kashghai rugs resemble Mughal textiles.

Village and nomadic carpets continued primarily for local use; export markets did not yet exist.

A UK Company That Sparked a Revival of the Carpet Industry

Economic Background

Mid-19th-century cholera devastated Iran’s raw silk export industry.

Carpets became an alternative source of national income.

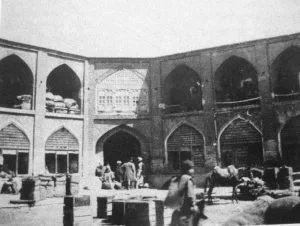

Ziegler & Co.

Manchester-based firm entered Iran after the Vienna International Exposition (1873) increased European interest in Persian carpets.

Opened a branch in Sultanabad (Arak) in 1883.

Manager Oskar Strauss initially bought antique carpets using gold from cotton sales.

As antique supply diminished, Strauss founded a carpet workshop, enabling large-scale new production

Impact:

Up to 2,500 looms operated at Ziegler’s peak.

Triggered widespread industrial revival across Iran.

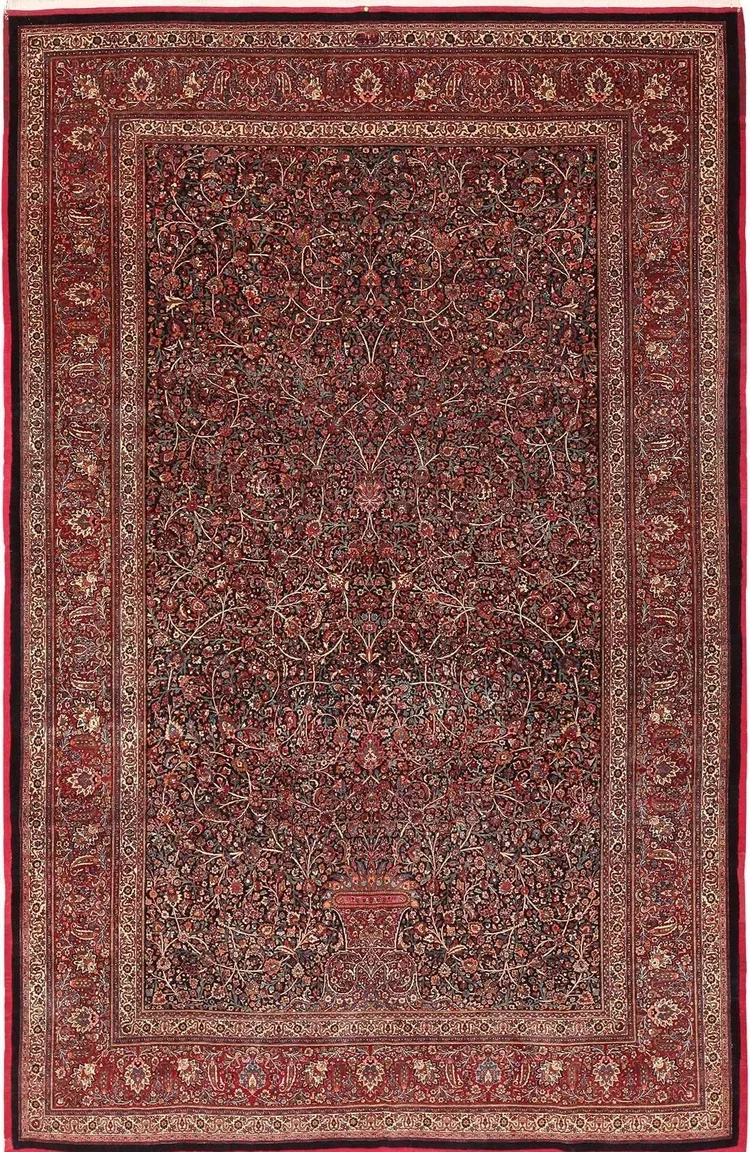

Rise of Persian Masters (Late 19th – Early 20th Century)

Numerous master weavers emerged (see Troves tab), but the most celebrated were the Amoghli Brothers of Mashhad, whose workshop became known as the best of the 20th century.

The Amoghli Brothers (Abdul & Ali)

Abdul, son of a silk merchant, began weaving in Tabriz before relocating to Mashhad in the 1880s.

Produced carpets with 1.2–2 million knots, exceptionally supple and refined.

Commissioned by Reza Shah for palaces and government buildings.

Despite their fame, the workshop closed in the late 1940s.

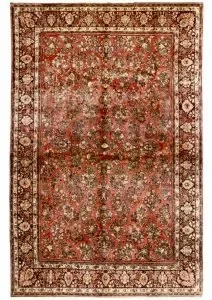

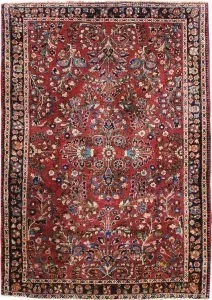

The American Sarouk That Influenced Persian Production

World War I Disruption

Iran’s export links with Europe collapsed as Germany (a major buyer) entered the war.

Creation of the American Sarouk

New York merchant S. Tiriakian commissioned rugs specifically for American tastes.

Designs featured rose-red fields and stylized floral branches.

Production boomed through the 1920s–30s.

Spread and Decline

Other regions, Kashan, Hamadan, and Kerman, adopted the style.

The 1929 Wall Street Crash ended the boom.

Design Evolution

1920s: Fern-like leaves from all edges.

1930s: Bouquet-filled fields, the modern Sarouk look.

The Rise of the Shah Dynasty

Political Shift

1921: Reza Khan, commander of the Persian Brigade, seized Tehran with the Bachtiari tribe.

Became prime minister, then Reza Shah, founder of the Pahlavi dynasty.

Renamed the nation Iran in 1935.

Institutionalization of Carpet Production

Founded the Iran Carpet Corporation (ICC).

Absorbed foreign companies like Ziegler & Co.

Introduced high standards:

Spring wool

Natural dyes

Uniform color standards

Major Achievement

Created the world’s largest carpet:

5,627 m², 47 tons, installed in the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque (2007).

ETFA Foundation

A state-run entity created in 1985 after the Islamic Revolution to preserve employment and craft traditions

Post World War 2

Reza Shah abdicated under Allied pressure; Mohammad Reza Shah succeeded him.

WWII destabilized weaving quality in major centers.

Iranian merchants migrated to Germany during reconstruction.

Notable mid-20th century weavers:

Alabaf (Tabriz)

Reza Sarafian

Hekmatnejad (Isfahan)

Fathulla Habibian (Nain)

Saber (Mashhad)

Notable designers included Issa Bahadori, Ahmad Archang, and Rassam Arabzadeh.

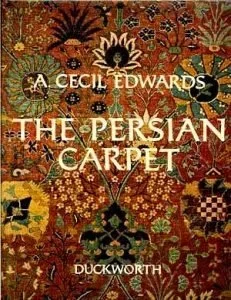

A Pioneer of Carpet Research

Arthur Cecil Edwards

Nephew of a founder of Oriental Carpet Manufactures (OCM).

Moved to Hamadan in 1911 to expand production.

Oversaw factories in Hamadan, Sultanabad, and Kerman.

Returned to Iran in 1948 to conduct extensive field research.

After his death in 1953, his wife compiled his findings into The Persian Carpet, now a foundational reference in persian rug history.

Post 1979 Revolution

Nationwide protests led to the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty.

Despite upheaval, master weavers like Seirafian and Hekmat Nejad continued producing fine carpets.

Industry emphasis shifted toward silk rugs.